NYS Immigrants and People of Color: New Unemployment Gaps During the Pandemic

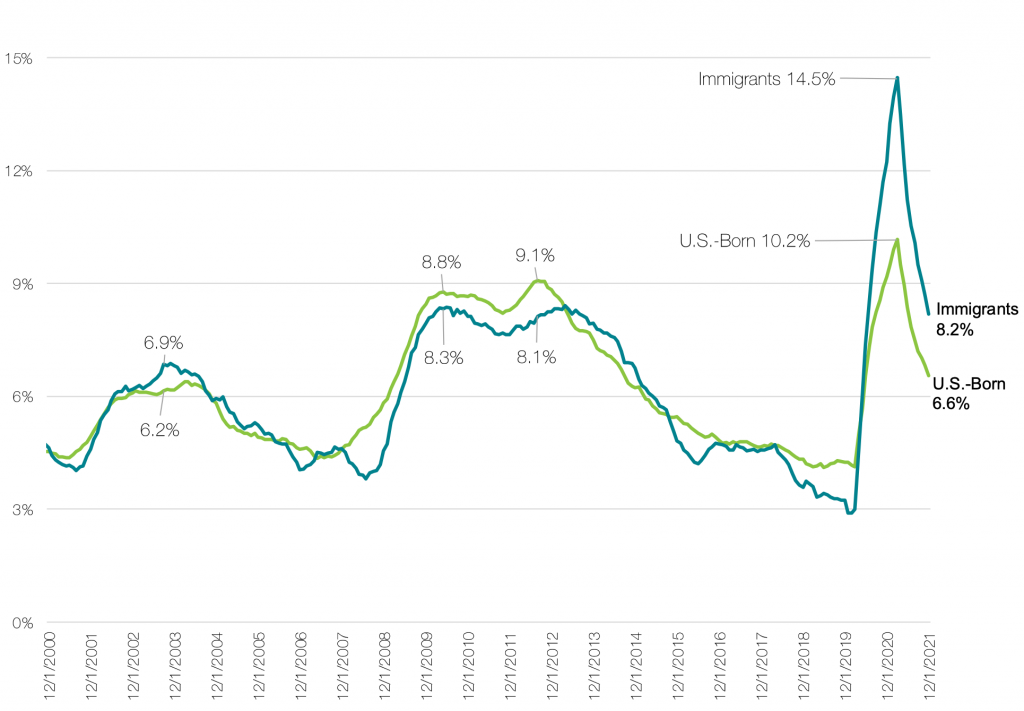

Job loss during the covid pandemic skyrocketed for all workers, yet for immigrants the unemployment rate spiked far higher than for U.S.-born workers. In New York, immigrant unemployment reached 14.5 percent at the peak in March of 2021, almost half again as high as the 10.2 percent rate for U.S.-born New Yorkers.

Typically, the unemployment rate for immigrants roughly tracks the rate for U.S.-born— sometimes a little lower, sometimes a little higher. Over the 20 years prior to the covid pandemic there was rarely more than a percentage point difference between the U.S.-born and foreign-born rates, and never more than two percentage points. During the covid pandemic the rate for immigrants was 4.3 percentage points above the U.S.-born rate.

And, while unemployment today has dropped from that historic high, the economy is still unsteady and the pain of joblessness in New York is far from over. The overall unemployment rate in New York State is 7.0 percent, well above the national level of about 4 percent.1Thanks to Julia Wolfe of the Economic Policy Institute for providing Immigration Research Initiative with the microdata analysis that underpins this report.

A Historic Spike That Hit Immigrants Hard, With Immigrant Unemployment Still Nearly As High Today As During The Great Recession

Data for this report uses a 12-month rolling average of the Current Population Survey (CPS) in order to look at detailed demographic groups and to account for the unusual nature of seasonal adjustments during the covid pandemic. The 12-month average is likely to understate the spikes of unemployment, and to show the highest level of unemployment later than would be shown using data from individual months. It also slightly overstates the difference between New York and the United States as a whole.2 The widely reported current national unemployment rate is 4.0 percent for January 2022. The national average using the same 12-month rolling average is 5.4 percent. The 12-month data does, however, address the difference between different race/nativity groups with statistical significance.

Fig. 1 Unemployment rates reported as a 12-month rolling average. Immigrants include all workers born in a foreign country, regardless of immigration status. Analysis of CPS microdata provided to Immigration Research Initiative by the Economic Policy Institute

The unemployment rate is a good indicator of the comparative impact of the recession on different demographic groups, but it is far from the whole story of how workers are faring. Unemployment rates reflect the share of people out of work who are actively looking for a job. That is always a partial picture, one that is complicated further by the fact that during the covid recession public health conditions often prevented people from looking for work in their occupations. A different window into the overall impact on workers: a recent report from The New School Center for New York City Affairs showed that there are over three-quarters of a million fewer jobs in New York State than there were 21 months ago—a larger job deficit than the state has seen in over 80 years, with all regions of the state seeing a deficit well above the national average.3James A. Parrott, “New York State’s Unprecedented Unemployment Crisis Requires a Comprehensive Immediate Active Labor Market Response,” The New School Center for New York City Affairs, January 13, 2022.

Why should the immigrant unemployment rate suddenly be so much higher than the U.S.-born? The answer likely lies in the fact that fewer immigrants are in jobs that allow them to work from home.

Immigrants are disproportionately represented in the two other job categories created by the pandemic: those in jobs deemed “essential work” during covid, and those where there were huge layoffs. Where they are under-represented is in jobs where it was possible to continue working from home. These job concentrations are high for immigrants overall, and higher still for undocumented workers.4See David Dyssegaard Kallick, “Spotlight on New York’s Essential Workers,” Fiscal Policy Institute, April 8, 2020; Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries,” Center For Economic and Policy Research, April 7, 2020; James A. Parrott and Lina Moe, “The New Strain of Inequality: The Economic Impact of Covid-19 in New York City,” The New School Center for New York City Affairs, April 15, 2020; and Donald Kerwin, Mike Nicholson, Daniela Alulema, and Robert Warren, “U.S. Foreign-Born Essential Workers by Status and State, and the Global Pandemic,” Center for Migration Studies, May 2020; Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock.

The Racial Disparities Were Different in this Recession

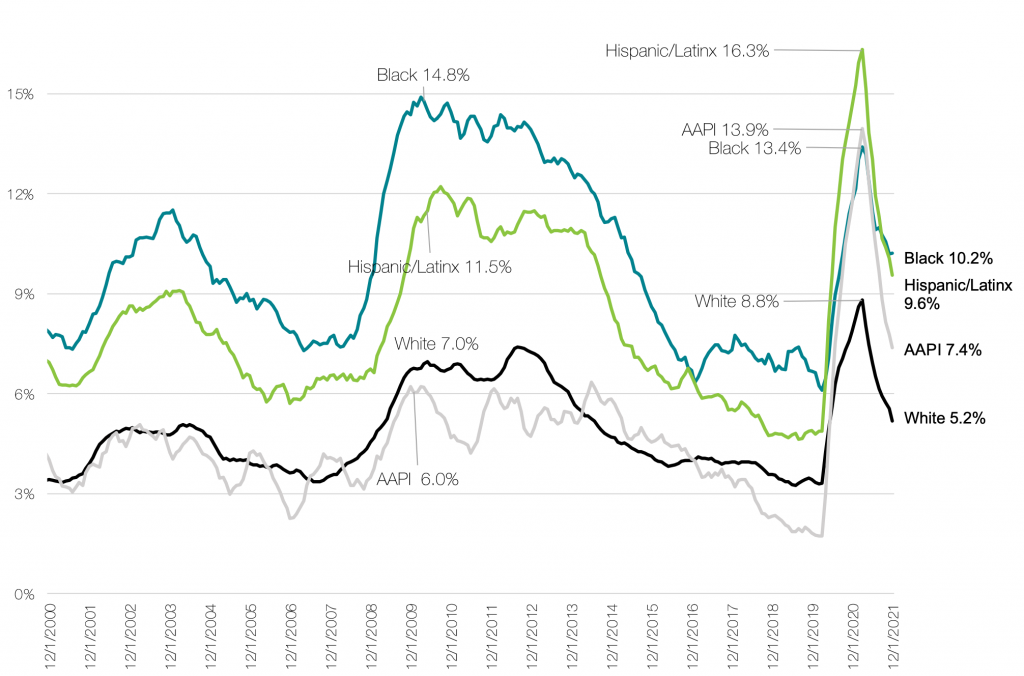

Racial disparities are deeply embedded in the labor market in New York as around the country, the result of decades of discrimination. Looking at the long-term unemployment trend, however, shows an added layer of racial inequity resulting from the covid pandemic.

Throughout most of the past two decades, tracking the unemployment rates by race shows the rates going up and down in parallel relative to the overall economy. Structural discrimination leads unemployment to be highest for Black New Yorkers and second highest for Hispanic/Latinx. Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) New Yorkers on average have had about the same unemployment level as whites, though there are big differences within different AAPI communities.

In the pandemic recession, however, the unemployment rate for Hispanic/Latinx New Yorkers (whether U.S.-born or immigrants) peaked at 16.3 percent, higher even than the rate for immigrants overall. The rate for Black New Yorkers peaked at 13.4 percent. And AAPI New Yorkers were for the first time in two decades clustered more closely with other people of color than with white New Yorkers, with AAPI unemployment peaking at 13.9 percent.

New Yorkers Of Color Slammed By Recession, With Aapi Unemployment Disproportionately Higher Than In Past Recessions

Fig. 2 Unemployment rates reported as a 12-month rolling average. Black, AAPI, and White are non-Hispanic portions of each group. Hispanic/Latinx can be of any race. Analysis of CPS microdata provided to Immigration Research Initiative by the Economic Policy Institute.

The current unemployment rate shows unemployment rates for people of color are still highly elevated. In New York State, Black unemployment is back at the top of the charts at 10.2%, Hispanic/Latinx unemployment is at 9.6%, AAPI at 7.4%, and white at 5.2%.

As with immigrant unemployment rates, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic is explained in significant measure by structural disparities in occupations by race: Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and AAPI workers are more likely to be in jobs that were deemed essential during the pandemic, and less likely to be in jobs where it is possible to work from home.5In addition to the above, see also Elise Gould and Jori Kandra, “Only One in Five Workers are Working from Home Due to Covid,” Economic Policy Institute, June 2, 2021; Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock, “Who Are Essential Workers? A Comprehensive Look at their Wages, Demographics, and Unionization Rates,” Economic Policy Institute, May 19, 2020; and Elise Gould, Daniel Perez, Valerie Wilson, “Latinx Workers—Particularly Women—Face Devastating Job Losses in the COVID-19 Recession,” August 20, 2020.

This report was first published on February 16, 2022 and revised on March 15, 2022.

- 1Thanks to Julia Wolfe of the Economic Policy Institute for providing Immigration Research Initiative with the microdata analysis that underpins this report.

- 2The widely reported current national unemployment rate is 4.0 percent for January 2022. The national average using the same 12-month rolling average is 5.4 percent.

- 3James A. Parrott, “New York State’s Unprecedented Unemployment Crisis Requires a Comprehensive Immediate Active Labor Market Response,” The New School Center for New York City Affairs, January 13, 2022.

- 4See David Dyssegaard Kallick, “Spotlight on New York’s Essential Workers,” Fiscal Policy Institute, April 8, 2020; Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries,” Center For Economic and Policy Research, April 7, 2020; James A. Parrott and Lina Moe, “The New Strain of Inequality: The Economic Impact of Covid-19 in New York City,” The New School Center for New York City Affairs, April 15, 2020; and Donald Kerwin, Mike Nicholson, Daniela Alulema, and Robert Warren, “U.S. Foreign-Born Essential Workers by Status and State, and the Global Pandemic,” Center for Migration Studies, May 2020; Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock.

- 5In addition to the above, see also Elise Gould and Jori Kandra, “Only One in Five Workers are Working from Home Due to Covid,” Economic Policy Institute, June 2, 2021; Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock, “Who Are Essential Workers? A Comprehensive Look at their Wages, Demographics, and Unionization Rates,” Economic Policy Institute, May 19, 2020; and Elise Gould, Daniel Perez, Valerie Wilson, “Latinx Workers—Particularly Women—Face Devastating Job Losses in the COVID-19 Recession,” August 20, 2020.